Contents | About | Contact

article 18, issue 06

Foundation building with human power: ground screws

Theo Schmidt

December 21, 2009 (last update 7.11.2012, new links 2.10.2025)

Abstract

Foundation

laying usually means much back-breaking digging even for small

buildings. Ground screws are a much easier method for supporting

lightweight buildings and are very suitable for installation with human

power. They are also easily removed and reused without using machinery.

Historically called screw piles, they enabled the rapid construction of

foundations for piers and bridges entirely by human power. They were

popular for nearly a century and then somewhat forgotten until

recently, reappearing for modern uses such as foundations for

photovoltaic arrays.

[Editors'

note: While we do cover stationary human power uses in HPeJ, this

rather static application may seem "off-topic". It is however a good

method for securing bicycle sheds and the like.]

INTRODUCTION

Foundations

for buildings or utilities are often made of poured concrete, sometimes reinforced with steel.

While these can be readily built using human power, there are

disadvantages:

- The production of the cement used in the concrete uses a great deal of energy.

- Considerable earth removal and preparation of concrete is normally required.

- When no longer required, the foundation is not easily removed or reused by human power.

There are alternative types of foundations which are especially suitable for construction using human power:

- Earth or ground screws (this article)

These are especially light and can be transported, implemented and reused entirely by human power. - Drystone construction (a future article)

Although

heavy, drystone constructions can be made of stones which are easily

transported, implemented and reused entirely by human power.

Ground screws

Ground screws are a relatively recent development combining properties of pile foundations and earth anchors.

Traditional

piles are generally used as deep foundations, e.g. the many vertical

oak piles the city of Venice is built on. They can support both by

transferring surface loads down to solid ground and by friction along

the whole length of the pile. Piles are often rammed in or vibrated out

using heavy machinery. Smaller piles can be rammed into the ground by

human power with large or special hammers. They can often be removed

with human power using winches.

Earth anchors are steel rods or wire

with helical or expanding anchors at the end or at several places along

the length. The former are screwed into the earth using machinery, the

latter can be rammed in by human power but are generally not

recoverable except by digging or breaking out. They are meant only for

tension loads, which can be in any chosen direction including

vertically upwards, unlike surface anchors or spikes which must be

loaded in a single, mostly horizontal direction.

Figure 1: Archimedes: "Give me a place to

stand on and I will move the Earth."

Ground screws

may be loaded in compression, tension, and shear. While they may be

installed using machinery, even large sizes can be screwed in with

human power. As already recognized by Archimedes: "Give me a place to

stand on and I will move the Earth." A great advantage is that they can

also normally be screwed out again by human power - and reused

elsewhere: a semi-mobile foundation. The screwing action also allows

adjusting the vertical depth to millimeter-precision.

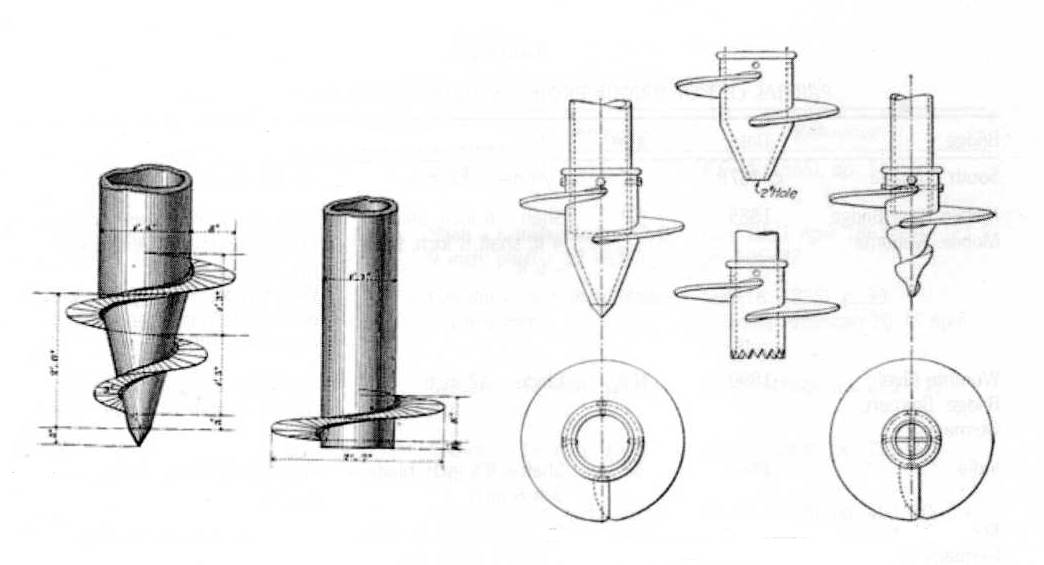

|  |

Figure 2: Earthscrews with flange (length of thread 0.5 m,

total lengths 0.8, 1.0 and 1.2 m, diameter of tube 75 mm)

|

Figure 3: Earthscrews (length of thread 0.4 and 0.5 m,

total lengths 0.8 and 1.0 m) |

Several types and many sizes exist. I used three each for

supporting a garden house, the flanged ones at the rear and the tubular

ones at the front. I bought various sizes, unsure whether I might hit

large rocks, but in the end was able to use the long ones everywhere.

All six were screwed right in. The front three received extentions in

the form of further steel tubes.

Figure 4: Garden house with 2.2 kW photovoltaic roof, total weight about one tonne

Inserting the earth screws is very easy. They screw with

little effort into the top soil. A spirit level is used to keep the

angle vertical. A short lever is sufficient intially.

|  |

Figure 5: Earthscrew being inserted. Note magnetic spirit level. |

Figure 6: Earthscrew nearly in. Note spring scale and water level (plastic tube). |

Our

soil is relatively "ordinary", a farm pasture with topsoil/grass, then

compact soil resting on a layer of conglomerate, frequent rocks and

some clay. After a few turns the thread begins to bite and the torque

rises quickly. A magnetic spirit level is used to keep the screw

vertical. This is easy as long as both arms can be used with a

symetrical lever. Soon a longer lever is required and unless two people

are available, torque on a single lever produces a force which tends to

misalign the screw vertically. If the lever can be easily transferred

to the other side, it is however possible to apply force such that the

misalignment is immediately corrected. Careful attention to the spirit

level allows a near perfect vertical angle and a lateral precision to

better than ± 5 mm. The vertical position can be very precise

simply by stopping at exactly the right position. Multiple screws can

be be brought to the same height with a long spirit levels, a plastic

tube filled with water, or a laser-level.

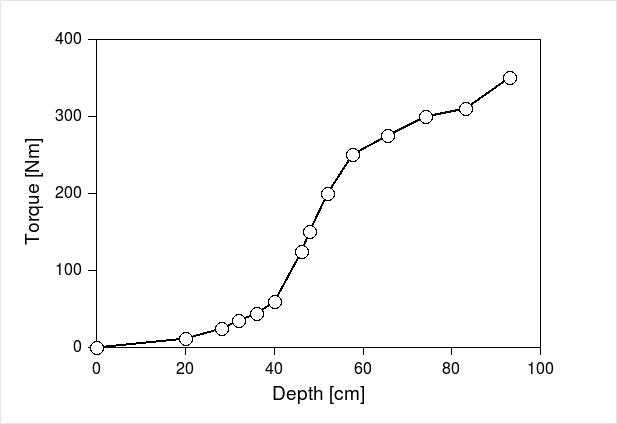

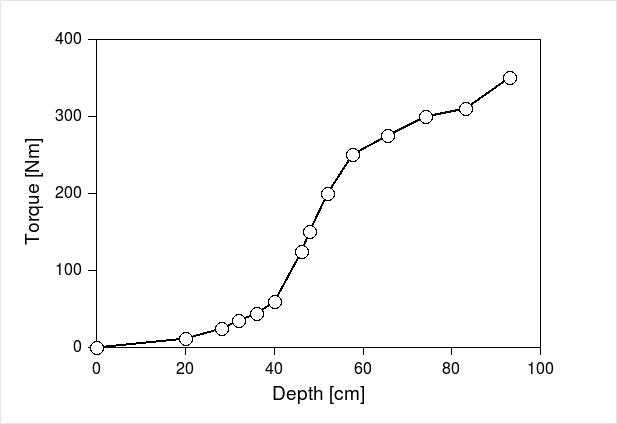

Figure 7: Torque versus depth. The last peak could be a rock,

some of the screws didn't go over 300 Nm.

Support Capacity

The obtainable loading is of course dependent

on the type of soil and on the length of the ground screw. The

following table gives some values when ground screws of similar type as

in the article are subjected to increasing vertical loads and these

measured when the screws have settled 5 mm and 10 mm.Table 3: Vertical loads at 5 and 10 mm settlement, several soil types and several screw lengths, from (Schulz 2004), Table A8-4

Ground

| Clay

| Clay | Clay | Sand, loose | Sand, dense | Gravel, loose | Gravel, loose | Gravel, loose | Gravel, dense |

Length

| 75 mm | 100 mm | 150 mm | 100 mm | 100 mm | 80 mm | 100 mm | 150 mm | 100 mm |

Settlement

| Load

| Load | Load | Load | Load | Load | Load | Load | Load |

| [mm] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] | [kN] |

| 5,0 | 6.1 | 34.0 | 84.0 | 15.0 | 19.5 | 3.3 | 6.2 | 9.6 | 51.0 |

| 10,0 | 8.1 | 42.0 | 100.0 | 18.8 | 28.0 | 4.1 | 7.9 | 11.6 | 87.0 |

Historical Development

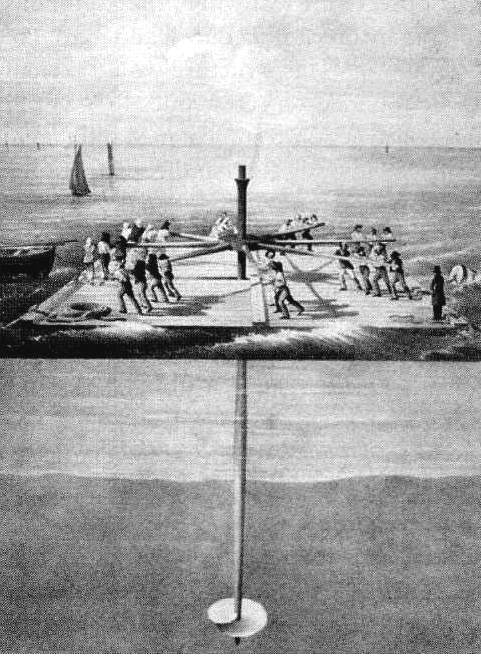

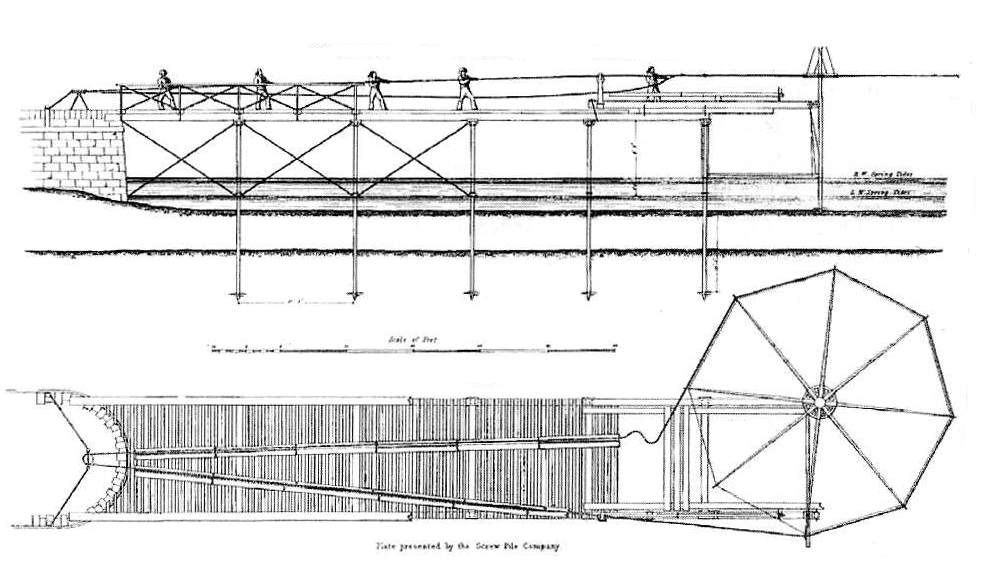

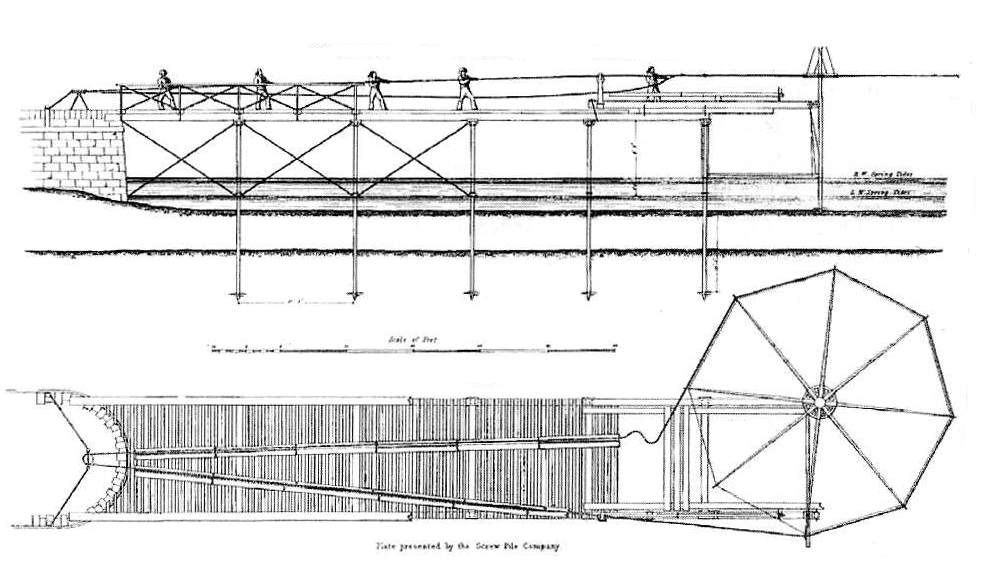

[All information in this section from Lutenegger (2011), also the figures in the Public Domain]

Ground screws, or screw-piles as they were then known, were first

developed by Irishman Alexander Mitchell from 1833. The first devices

were used for mooring ships and loaded only in an upward direction. The

screw's thread had little more than a single turn and was screwed into

the sea-ground with a temporary shaft later removed.Figure 8: Several forms of screw-piles

Later

the shaft became the foundation pile itself and these were used as the

foundations of offshore lighthouses. One of the first, the Maplin Sands

lighthouse was mounted on nine such iron piles, each about 13 cm

diameter and with a screw flange of about 1.35 m diameter. Each screw

pile was screwed into the sea ground with eight capstan-like levers of

3-5 m length. Figure 9 shows such an arrangement worked by 32 men. Over

60 lighthouse foundations were built in this or a similar manner in

Great Britain and USA.

Figure 9: Capstan on plattform built on two barges, worked by 32 men.

Later

screw-piles were used for pier and bridge foundations. The barge method

of installation prived impractical in a seaway and methods were devised

to work from land, installing the first screw-piles, building and

extending the structure and working from this as it grew. An endless

rope was attached to the capstan and this pulled by men and later

animals or machines. Dozens of screw-pile piers and bridges were built,

some of them famous constructions still in use today.

The

screw-pile technology was in use and known well into the 20th century.

Then it was forgotten for a while until some years ago German Klaus

Krinner developed the form shown at the beginning of this article.

These are now used for all sorts of lightweight constructions such as

fences and photovoltaic arrays, but also buildings.

Figure 10: Method for extending pier from land, installing screw-piles with capstan worked by endless rope.

REFERENCES

Contents | About | Contact

Human Power eJournal